As part of our June 2023 Crete expedition, we visited five caves in the northern part of the island, each of which was different in shape, size and faunal composition. Crete is a fascinating place for its cave fauna, with a varied and often endemic species mix, and the accessible caves on the island provide a small taste of this limestone-based underground world. As always, casual spelunking is an activity which should be undertaken with particular regard for safety: appropriate equipment (torches, sturdy shoes), attention to weather conditions and local geology, spotters, maps...

1. DOXA

The first cave we visited was Doxa, in Marathos. We stopped in the little taverna next to the cave, and ordered some drinks before asking if it was OK to visit. The cave entrance is located down a short and quite steep set of steps and trail which goes down past the taverna and underneath it. Inside it is quite steep for the first few metres, and was quite slippery in places.

I managed to find Philaeus chrysops on the way down. All the individuals I saw of this species on our trip were very washed-out looking and pale.

The cave was an interesting little one, with lots of stalagmites and stalactites, some of which had been chopped to make public access easier. It was damp, but the air was quite light. There was a low ceiling at one point over a shallow puddle of clear water, which required us to crouch and crawl, and in the large end chamber was a single horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus sp.) sleeping on the ceiling.

We found little in the way of cave-adapted invertebrate species during our visit. Tom found the small isopod Trichoniscus lindbergi.

Previously, other explorers of the cave have found the pseudoscorpion Neobisium (1, 2) and endemic spider Savignia naniplopi, which is only known from Doxa and the adjacent Arkalospiliara.

2. MELIDONI / GERONDOSPILIOS

Just under two kilometres northwest of the village of Melidoni is the Melidoni cave, also referred to as Gerondospilios ('Old Cave'). The car park and adjoining cafe and facilities are siruated at the end of a sweeping balcony road with panoramic views of the plateau and far-away hills, at an elevation of approximately 220 metres.

A large limestone cave with a rich history, there is evidence of Neolithic occupation, as well as being considered a middle Minoan religious site. Various inscriptions in the cave on rocks and walls are readily visible to visitors, although some are hard to spot. Talos, the bronze guardian of Crete, is said to have resided there when patrolling the shores of the island, and there are connections to the Roman worship of Hermes. In recent centuries however, it has been better known as the location of the 1824 tragedy in which nearly 400 people took refuge in the cave from the Ottoman army. After three months and no surrendering from the Cretan residents, the troops lit a fire at the entrance, and all inside suffocated. Inside the main cavern is an ossuary in which the remains of those who died are kept, and the sacrifice of the victims commemorated. More information n be found here.

Above: the main gallery of the cave, and a cave map from here. (image only link)

The area directly around the entrance is scrubby and dry, with a lot of loose rocks. Just outside this entrance we finally found some scorpions – I had been wondering when they would turn up, as we so far hadn't seen any on our trip. These were small and quite pale-looking Euscorpius candiota, quite easy to mistake on first glance for the more venomous yellow scorpions. One of these was feeding on an Armadillidium sp. woodlouse among a collection of other invertebrate remains, presumably evidence of not only what the scorpion had been eating recently, but also betraying its somewhat stationary nature. After all, why waste energy and risk dessication actively hunting, when you can wait out the heat in the humid space under a rock and eat everyone else who has the same idea?

I was very interested in the fact that the brochure we were given at the ticket office featured a specialised blind cave-living Dysderidae called Minotauria, and wondered whether it was possible to find one in the cave or whether the out-of-bounds areas served as protection areas for the species. It was excellent to see spiders getting positive publicity.

Text:

"MINOTAURIA ATTEMSI FAGEI

The cave is home to a medium-sized species of blind spider from the Dysderidae family. It was first located in 1900, in the 'Labyrinth' cave of Gortryna, by the Austrian entomologist Carl Attems, who named it minotauria, because of where it was found. This species is found in Melidoni cave, as well as other caves in central Crete."

Inside the cave it was slightly cooler, a real break from the windless heat outside. We descended a large, well-made set of stairs and raised rough stone paths which guided visitors around the cave and provided signposts at various locations. Towards the entrance where the light still filtered in, there were a lot of sheet webs inhabited by some truly huge Tegenaria spiders. Some were so large-bodied that had they been in darkness they would be easy to mistake for Cave Spiders (Meta sp.) - although interestingly, we never saw any of these on our trip.

The central hall of the cave was an airy, open cavern, fringed with lumpy columns of rock, which up close sported tiny holes and secret miniature tunnels. With over a millennium of anthropogenic history in the cave, it is difficult not to feel amazed and overwhelmed by how important Melidoni has been to so many different groups of people over time, and how the significance of the cave has continued into the present day, with the cultural, geological and scientific value.

As the majority of the cave floor was roped off and the adjacent rooms inaccessible (the only public gallery was the Heroes Room, 6 on the map), we weren’t really able to look around for cave fauna. I had discovered a good technique for finding many things in caves the previous year in Madeira: looking for outside organic material such as wood lying on the cave floor. Life tends to proliferate around organic material in the dark, which must make a very tasty change from bat droppings. Sadly (but not entirely unexpectedly) with the exception of a few small rodent skeletons there was no other organic material in this cave, and definitely no wood. However, we did spot somebody’s old, mouldering fabric hat lying just off the path, which was certainly worth a try. Reaching down and flipping it over with my foot, the only thing that came scuttling out from underneath was… the endemic cave spider Minotauria!

The spider ran at first when I moved the hat, but quite quickly calmed down and started to walk about as normal. Not having any eyes meant that it shouldn't be able to tell when the torch was on, so it walked right up to my shoe and nearly onto the path (where it was guided back to safety). The long and rather slim legs were used to feel the terrain in front, and I assumed a 'grab first, ask questions later' policy applied to its feeding habits. Despite the presence of a woodlouse spider, Tom wasn't able to find any actual woodlice, so any species present are ore likely to be further back in the chambers, away from the artificial lighting. According to the 2013 Spiders of Crete publication, the spider we saw would seem to be Minotauria fagei.

Some reviews on TripAdvisor have the bonkers opinion that the 4€ entry fee is a bit high. I think that having the opportunity to not only experience the history and beauty of this cave, but also be able to see an endemic eyeless woodlouse spider for only 4€ is an absolute bargain.

3. CHAINOSPILIOS

Also spelled Hainospilios, and also sometimes called Marmarospilios, this historic cave is situated just outside Kamaraki village. Like Melidoni, it was also used as a hideout from Turkish troops for local villagers during Ottoman times. The name of the cave refers to this use, from 'Chainides', Cretan rebels. The cave is comprised of Miocene (12 million years old) limestone and is part of an underground river system, apparently still active in some areas, which has resulted in the smooth tunnels and walls inside.

This cave is not public access; there is a little taverna in the village where you can ask to borrow a key to the gate. Once again, we ordered some drinks and lunch beforehand - after all, it's not only polite to do so, but more sensible to explore a cave on a full stomach and with a clear head. The village was beautiful and peaceful, with no traffic noises.

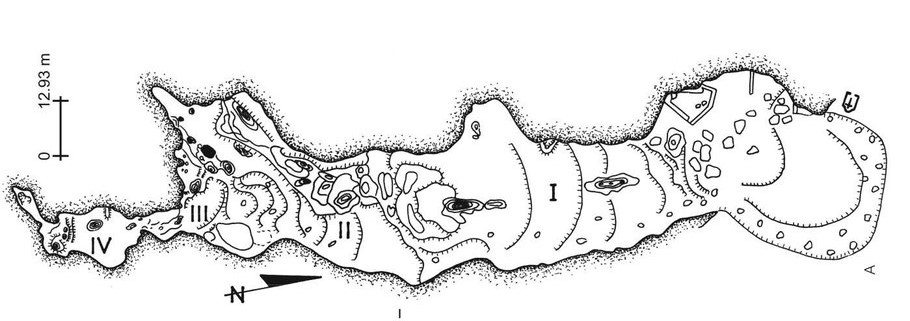

Above: the taverna, and a map of the cave from here.

We headed up the road (no more than 300 metres or so away), and found the entrance to the cave, which was so well-hidden that I almost missed it walking past. Outside, underneath a fallen sign Tom found a few more Euscorpius candiota, and we also saw some Lymantria dispar larvae and a beautiful marbled cricket, which seemed to be a mysterious and exciting species we had never seen before.

It was a small entrance which went sloping gently downhill. In the past, some wide stairs had been cut into the stone, which led into the first chamber. In all of the cracks and crevices were many of the same marbled cricket species we had seen outside, which were now recognisable as cave crickets (Troglophilus spinulosus), one of apparently only two species found on the island. Somehow out of the cave they seemed very alien; they must leave seldomly. The one under the sign was very close to the cave entrance, so it probably left at night and then sought shelter in the nearest dark space when the light returned.

There were offshoots and tunnels everywhere, including large tunnels in the roof, and water on the floor, reflecting the torchlight onto the ceiling and creating strange patterns of light. Without a paper copy of the map, it gave the impression of being a labyrinth of tunnels which you could easily lose yourself in - and indeed, one of the local names for the cave is 'Labyrinth', although the main hall is actually only around 200 metres in length. Another, slightly shorter hall of 120 metres apparently runs parallel to this one, but unfortunately we didn't see the entrance to this tunnel and therefore weren't able to explore it.

Interestingly, the older archaeology inside the cave has been little-explored, although it clearly has archaeological merit. There were lots of pottery pieces and animal bones on the floor, some of which looked very old (according to this website, Pre-Minoan, Late Minoan I, Roman and Byzantine). We left everything in its place.

Tom managed to find a beautiful tiny Graeconiscus caecus (which he took far better pictures of than I did) and some tiny white snails. At least four species of bat have been recorded in the cave - three species of horseshoe (Greater Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Lesser R. hipposideros, and Blasius's R. blasii) and Lesser Mouse-eared Bat (Myotis blythii), but I saw none in the main gallery during our small exploration.

To get a general feel of the cavern, and to experience somewhat how early explorers of the cave may have felt, I turned off my torch and stood in the darkness for a while. There was no light, no sound except for the occasional muffled drop of water on the rock floor. Without the torchbeam it seemed doubly eerie and atmospheric, with an unseen recognition of standing in an open space but no indication of exactly how large the chamber was. When I turned the torch back on again, colours on the walls seemed incredibly saturated, and it was easy to pick out unusual shapes in the limestone formations. Caves certainly have a peculiar effect on people; small wonder we've been drawn to them since the dawn of time.

4. SKOTINO / AGIA PARASKEVI CAVE

From small to large; the entrance to Skotino (Skoteino) cave could not be more different. It is public and open-access, situated in the middle of open dusty scrub habitat adjacent to the Saint Paraskevi church, and immediately obvious as a great yawning mouth of the landscape, inviting visitors in. By way of introduction, including maps and archaeology of the cave, I found this paper to be highly useful and greatly interesting.

Above: The entrance to the cave, and a map figure from here.

Despite looking relatively shallow, Skotino has a lot of dips and curves, and some tunnels at the back down a steep slope which weren't accessible to us on foot. The total length is approximately 200 metres. The interior space of this cave felt very different to the other ones; for a start, the entrance was so large that there was some degree of light all the way to the back, and torches weren't necessary for much of the descent. Secondly, despite access to the fresh air, there were some areas under the ledges and in other areas that felt decidedly stale. This cave seemed strangely promising for bat roosts, but again I fell short - there may well have been roost sites at the back where the tourists generally couldn't reach.

Throughout the whole cave, from just outside to deep within, were enormous beetles of the Tenebrionid genus Blaps. Commonly known as churchyard beetles in Britain, they are very unfussy in diet, eating organic matter.

Getting further inwards here involved a bit of a scramble over slightly slippery and generally quite smooth rocks. On the walls were plenty of crickets, this time the other species of cave cricket found on Crete: Dolichopoda paraskevi, the type specimen of which was found in that very cave. Their antennae were impossibly long, and their hunched-looking bodies shiny and almost damp-looking.

Under the shelf-like rocks in a slightly foetid smelling area were plenty of woodlice (Schizidium perplexum and Bathytropa granulata), and, to my surprise, another Minotauria, which wandered out from underneath. Once again, its movements were generally quite slow, feeling about a lot with its slightly extended legs. This one wandered into the path of a cricket, and had a gentle exploratory nibble on one of its legs, which the cricket did not take too kindly to. Zooming in on the picture, the marks on the cephalothorax are not eyes, but appear to just be pigment under the carapace. This species would seem to be M. attemsi, according to the Spiders of Crete paper.

Above: Presumed Minotauria attemsi, pseudoscorpion, Bathytropa granulata, Schizidium perplexum, pholcidae

This cave was an interesting one; with patches of organic matter and clearly a wide range of cave fauna, it got progressively more interesting the further inside we went. Had we had any way of getting down the steep slope at the back into the lower levels, we may well have discovered some other interesting creatures in there.

Above: Tegenaria? in the mouth of the cave where it was still light, but had a cool breeze.

5. ARKOUDOSPILIOS

Our fifth and final cave was Arkoudospilios, located on a very exposed hillside trail conecting two monasteries, Gouverneto and Katholiko. There was an entry fee as the monastery is active, and you are also advised to wear modest clothing (e.g. no shorts above the knee).

As this was a short trip on the same day as we were flying back, I didn't take a great deal of pictures. The cave had a wide entrance near some ruins and didn't go as far back as the others, although there was a single low tunnel at the back. There were some interesting rock formations, including the large bear-shaped rock behind a small puddle in the entrance. It was clearly used frequently by goats (and humans) as a spot of relief, so the floor had a rather soft texture. We would have benefitted heavily from latex gloves here for rolling rocks - I had to wait a while before being able to do some extreme hand-washing after we exited. Not a mistake I will make again!

Because there was so much animal waste and organic material in the cave, finding anything in here was difficult. We found fairly good numbers of the isopod Trachelipus cavaticus, and I was initially excited to turn up another dysderid spider, pale and elongate, but upon closer inspection this one had a definite cluster of tiny eyes, so was not another Minotauria. However, it was quite pale, and was hanging around at the back of the cave - some sort of transition between the outside life of the other Dysderidae and the cavernicolous darkness of Minotauria's existence? Or perhaps it had just wandered in from outside after hearing that this was where the juiciest woodlice were.

In the cave entrance were several species taking shelter from the heat of the outside: a potter wasp collecting mud from a drain, and an Oriental Hornet (Vespa orientalis) taking water from algae growing on the low-lying ceiling.

Outside the cave under a rock we found the very common Armadillo tuberculatus; this was a large specimen, but otherwise quite unremarkable as they were quite abundant under rocks and on walls during the night. However, while it was being held as we replaced the rock, I heard a sound I couldn't place until Tom informed me that it was the woodlouse itself that was making the noise. Stridulation is well-documented in the Armadillo genus, and they are only able to produce the noise while rolled into a ball, suggesting that it may be a secondary defence mechanism or method of signalling danger to other individuals. It sounds extremely similar to the stridulations produced by land hermit crabs (Coenobita sp.), which is commonly recorded in captivity. Luckily, this one was in no real danger, and was put back under his rock after this little video was taken.

Crete has a huge number of caves (around 3000); the five we visited here were located quite close to one another, and thus we barely scratched the surface of the island's subterranean world. Cretan mythology and history was intricately entwined with the names of the caves and their inhabitants, from the real 'Labyrinth' of Chainospilios to finding Minotauria lurking in the dark, and a unique atmosphere was evident inside each different cavern. You could spend decades exploring Crete's caves. There is likely to be far more interesting fauna inside other less frequently-visited caves, and the island has proven hugely biodiverse, with plenty more to discover.